Tools I Used

ATLAS.ti

Figma

Miro

Procreate

Duration

August - December 2020

What I did

User Interviews

Literature Review

Storyboards

Qualitative Data Coding

Journey Maps

High-Fidelity Prototyping

Usability Testing

Team Members

Kaely Hall

Kyle Kohlheyer

Jiaxi Yang

Overview

Here, I’ll introduce the scope of this project. Keep scrolling to read a Deep Dive into the details!

Problem Space

As part of one of my core classes — HCI Foundations — in the Georgia Tech MS HCI program, my team was tasked with a semester-long user-centered design project. My team chose the prompt “Help connect Georgia Tech students with on-campus mental health resources,” because we had a shared passion for using design to better people’s mental health.

Our literature review and preliminary interviews affirmed the need for a solution in this space. Mental disorders, which are associated with diverse long-term negative consequences, are very common among college students, and although interventions are widely available, the majority of students do not receive treatment. These trends were confirmed in our interviews with Georgia Tech students.

Solution

My final high-fidelity prototype included several features, some of which are shown below. Keep scrolling to take a look at our overall process!

Screening Questionnaire

Screens users for severe mental health issues and refers them to the appropriate resources

Allows users to select their health care interests

Our mascot encourages users and maintains the welcoming tone.

Emergency Resources and Login

Makes emergency resources as accessible as possible

Custom-designed mascot makes the app feel welcoming

Progress Tracker and Home Screen

Users can track their progress and easily access their next steps to care

Encourages users to continue on their journey by providing positive reinforcement

Building a Mental Model

Educates users about GT’s mental health care system

Level sets users’ expectations of the help-seeking process to avoid disappointment and confusion.

Deep Dive

Research

Understanding the problem

First, my team undertook a literature review and competitive analysis. I researched meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding mental health in college students and bolstered our understanding of our general user characteristics, user goals, and socio-cultural context.

Who are our users?

Georgia Tech has a very demographically diverse student group. In 2019, about 25.1% were international students, 53.5% residents of another state, and 60% underrepresented minorities. Diversity matters because help-seeking behaviors for mental wellness vary across demographic backgrounds. Some cultures may have a more stigmatic stereotype about mental problems.

What is their problem?

Mental illness diagnoses among college students have been rising since at least 2017, and the pandemic has only exacerbated this trend. New students have fewer opportunities to make friends, and factors such as ill loved ones, economic hardship, or increased familial burden could negatively affect mental health. However, most students with mental health issues are aware of their need for treatment but “do not receive treatment, even over a two-year period” (Zivin et al., 2009).

Why don’t our users receive help?

The most common reasons are related to the stigma of mental illness and embarrassment of seeking mental support. The association of mental illness with weakness, unprofessional, and failure makes many people reluctant to admit, or even realize, their struggles. This reluctance to seek help can be so intense that even intentions of providing help “can bring greater sense of shame and failure” to some students for “letting down [their] caring ones” (Rosenbaum & Liebert, 2015). Even for those who are aware of their problem, 56.4% prefer to handle it alone and talk with friends or relatives (48%) (Ebert et al., 2019).

Additional factors include limited knowledge or misunderstanding about mental wellness resources, uncertainty about the right steps to start, and concerns about financial cost. Some students are also concerned about conveniences for scheduling and transportation.

For those with a past of good mental wellbeing, limited knowledge of mental illness could lead to poor sensitivity about emerging problems (Gulliver et al., 2010). During the pandemic, when unpredictable and unwanted changes are part of life, extra resources are needed to maintain mental wellness beyond simple self-assessment.

Interview data qualitative coding

Requirements gathering

Interviews

Next, we interviewed 6 users (all GT students) and 1 expert from GT’s mental health system. 2 of our interviews were contextual interviews, in which we dived deep into the user’s prior history of seeking mental health help. Our goal was to understand the users’ lived experiences in as much detail as possible. These interviews covered a lot of sensitive and personal information, so designing high-quality interview questions was paramount.

Building on this research, we analyzed it by first qualitatively coding our interview data. I coded my interviews in ATLAS.ti to group the data chronologically and thematically, and one of our research artifacts can be seen to the right. Although the word cloud does not convey much data on its own, it represents the scope of the conversations we had with our interview participants.

User journey map (click to enlarge)

Analysis

Next, faced with the conundrum of how to analyze the rich qualitative data that we had collected, I came up with the idea to use journey maps to compare users’ lived experiences with the process as GT intended it (via our expert interview). This comparison made discrepancies between users’ experiences and the intended process immediately obvious.

This method of analysis also kept users’ experiences within their specific context and timeline, which other methods like affinity modeling would not have accomplished. I felt this was crucial to understanding the users’ experiences — anything less would not have been true to the way their experiences changed over time.

The weak points in GT’s intended process would become the focus of our design. They include

Impact: These discovered weak points led directly to the creation of our design requirements, which would guide the rest of our project.

Mental model mismatch: there exists a mismatch between the actual process of getting help and students’ mental model of the process. This extends from the high-level (confusion about the intake procedure as a whole) to the specific (misaligned expectations of group therapy’s benefits).

Impersonal communication: making an initial appointment lacked a personal touch, and students did not feel truly cared for.

Intensive process without reward: the intake process required several steps and significant time without rewarding the student with assistance. This caused some students to become discouraged.

Off-campus referrals: Unfortunately, GT does not have the capacity to help all students on-campus. Therefore, GT refers some students to off-campus resources. This process has the potential to be positive, but students currently find it to be impersonal and a delay on them getting help. Being referred caused several interviewees to pause their help-seeking altogether. Again, a personal touch was missing.

Research Takeaways

Design

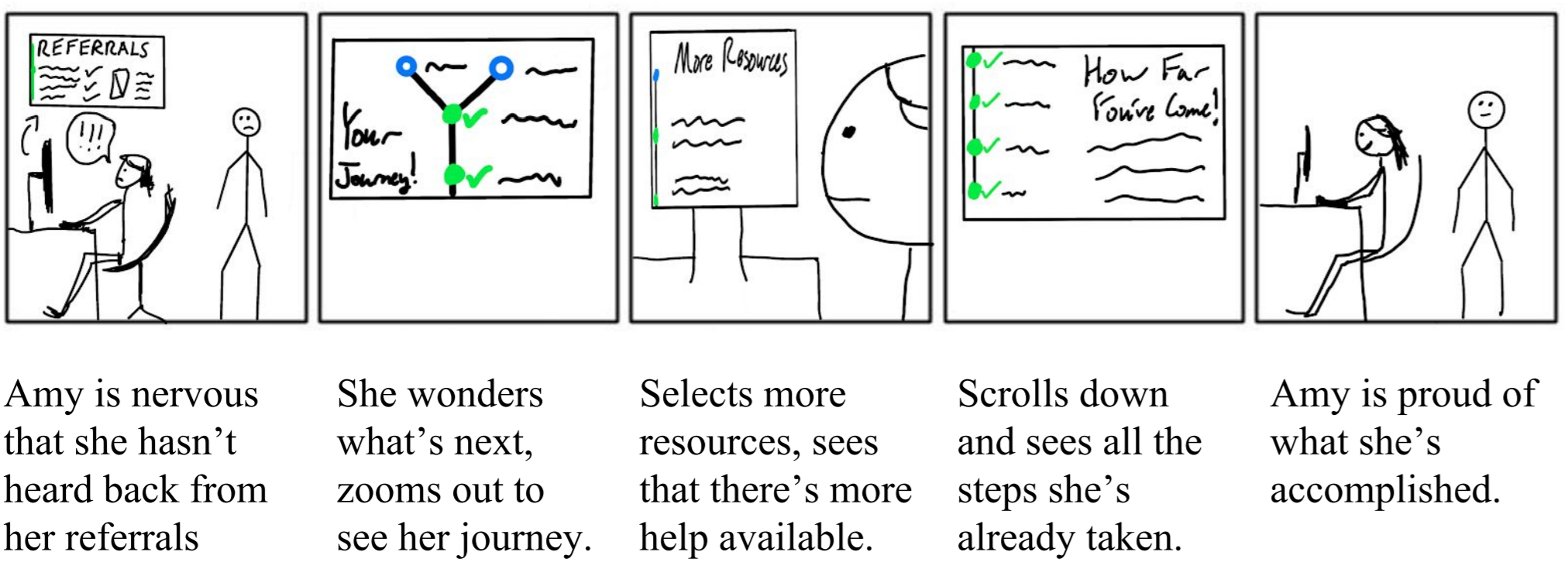

Impact: The storyboards gave our team a window into the lives of our users and made abstract design requirements into concrete details.

Design brainstorming

Based on our research findings, my team came up with a number of divergent, wild ideas for solving our problem. Over time, we narrowed them down, combined them, and arrived at our final two ideas.

I illustrated our ideas in storyboards using Procreate for iPad. Although I am not a trained artist, I did my best to follow our design requirements and to convey the benefits and intended uses of our designs.

Design Language

Before creating the prototype, I also created a design language to address many of our expected design challenges and needs. Although not all of these designs made into the final prototype, many did.

High-Fidelity Prototype

Impact: Proof of concept, supported further research into the efficacy of our design requirements

Using the design language, I created a high-fidelity prototype from scratch. Click through it here! My driving goal was to enable further research by staying true to our design requirements and previous research.

Sign Up & Screening Questionnaire

Home Page

Online Scheduling

Emergency Resources

Evaluation

Impact: Gained actionable feedback — within time constraints — on system design and usability with respect to our design goals.

Finally, my team performed a discount evaluation — we used our classmates as users. This process gave us intense insight into the real life of UX Researchers. Often, you have to make the best of a less than ideal situation. Nonetheless, we did our best to ground our users in our app’s context of use.

We led users through three benchmark tasks, designed to test the main features of the system.

Learn about GT CARE and make an appointment.

Imagine you have completed your GT CARE appointment. Now find out what you have previously accomplished and determine your next step.

You are in an urgent mental health situation and you feel your life could be in jeopardy. Complete the onboarding process with the goal of locating and connecting with the appropriate emergency services.

After each task, we administered NASA-TLX questions as a subjective measure of task load.

At the end of the activity, we administered the System Usability Survey (SUS) to understand the perceived usability of the system.

Reflection

Through this project, I stretched myself in every possible direction. I expanded my research capabilities, came up with novel ways of analyzing qualitative data (comparative journey maps), and designed a high-fidelity prototype from scratch. All of these skills will make me a better researcher going forwards. In particular, getting to design after so much research was incredibly gratifying and gave me a window into the life of a designer. I now feel much better prepared to give designers actionable research analysis.